|

Home page About us Instruction Guiding Locations map Gift vouchers Prices Articles Contact us Accommodation Links |

|

||||||||

Lessons from America. An appreciation

of two books:

I

have chosen to highlight these two books

because they complement each

other and

extend

the messages we try to convey in our all-too-brief guiding and

instruction sessions on UK rivers on and around Dartmoor in Devon. I

have chosen to highlight these two books

because they complement each

other and

extend

the messages we try to convey in our all-too-brief guiding and

instruction sessions on UK rivers on and around Dartmoor in Devon. |

John

Gierach's "Fly Fishing Small Streams" is a beautifully

constructed

mixture

of 'how-to' information and

mental approach to small

stream fishing. For example, Gierach has a refreshing approach to the

'lunker'

mentality:

John

Gierach's "Fly Fishing Small Streams" is a beautifully

constructed

mixture

of 'how-to' information and

mental approach to small

stream fishing. For example, Gierach has a refreshing approach to the

'lunker'

mentality:

"So let me

introduce an idea - just something to kick around: Maybe your stature

as a fly fisherman isn't determined by how big a trout you can catch,

but by how small

a trout you can catch without being disappointed, and,

of course, without losing the faith that there's a bigger one in there".

(From 'Fly Fishing Small Streams").

We are lucky because Dartmoor's rivers teem with

small trout, which at times can be free rising and liberate

childish delight in all of us. And there are occasional bigger trout

in surprising places. Last season a colleague returned a 14" trout

within yards of a normally busting tourist honey trap, and there is

always the possibility of hooking a sea trout. Here's our take on the

subject of brown trout size in local rivers.

Time is short in instruction sessions. We constantly feel under

pressure

to teach purely mechanical skills - controlling wrist break or

tying knots that won't slip. Just as important is the need for

stealth when approaching and entering the water. Often the best thing

to do is simply stand still and do nothing. But fifteen minutes of just

standing and staring would be hard to justify in a short

session. Gierach devotes an entire chapter to this important

topic which begins:

He has useful things to say about many topics including: etiquette, casting a dry fly downstream rather than the conventional upstream approach, the use of streamers - a very underused technique, and the perennial problem of choosing a rod for small stream fishing:

Gierach's chapter on fly selection is refreshingly honest. He describes two familiar stages of developing an appropriate fly collection that - believe me - we all go through: Stage 1 is 'thrashing around' collecting every fly known to man and buying ever-more complicated and expensive fly boxes. I have found myself seriously considering buying a box designed to keep water out, despite owning a much simpler fly box that was carefully constructed to allow water on flies to drain out! Some folk progress to Stage 2 which involves 'over-simplification' - a tiny collection of patterns based on the theory that trout in small streams are 'generalists' and will eat anything that floats past them. Or, as Gierach puts it:

I confess to almost becoming stuck at this 'minimalist' stage of development. If you find yourself in a similar predicament, take a look at Ed Engle's "Fishing Small Flies".

This may help us progress to Stage 3 - Matching the Hatch.

One unique feature in Engle's book is the series of "Match the Life Cycle" diagrams that summaries the life cycle, patterns and fishing tactics for the types of insects we encounter on Dartmoor rivers and streams: ephemeroptera, midges, and microcaddis. We may not really need to closely match the hatch, but it helps boost confidence - and gives a new dimension to the richness of the fishing experience - if you have a rationale for using a particular fly presented in a particular manner.

Engle devotes an entire chapter to the

importance of taking time to watch how

trout rise; this may give a clue as to the insects they are feeding on,

and

perhaps more importantly where they are feeding - taking insects on or

just below the surface. He draws on Marinaro's

distinction between simple, complex and compound rise forms and repeats

Marinaro's explanation that these different forms reflect the trout's

level of suspiciousness

about the (artificial) fly.

Engle devotes an entire chapter to the

importance of taking time to watch how

trout rise; this may give a clue as to the insects they are feeding on,

and

perhaps more importantly where they are feeding - taking insects on or

just below the surface. He draws on Marinaro's

distinction between simple, complex and compound rise forms and repeats

Marinaro's explanation that these different forms reflect the trout's

level of suspiciousness

about the (artificial) fly. I am a great admirer of Marinaro's work, but I might quibble with the idea that trout are suspicious. Certainly it looks like suspicion from a human point of view. But it's difficult see how this behaviour would have evolved in trout. I prefer the simpler explanation that variations in rise forms are due to the trouts' visual system, environmental factors such as the rate of current flow, and the structure of different insects. But then I am known as a bit of a pedant about this type of thing!

The important point is that Engle's chapter on observation together with Gierach's chapter on stealth and watercraft will help you get more enjoyment from your fishing.

Engle stresses simplicity in his choice of tackle. For example, he goes into great detail on leader design. But his open-mindedness shines through when he admits that he "still goes back and forth" about the merits of knotless over hand tied leaders. He gives the following down to earth advice:

The problem of 'drag' figures prominently

throughout the

book. For example:

The problem of 'drag' figures prominently

throughout the

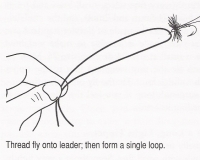

book. For example:Engle also reproduces the full instructions for tying the surgeon's loop or double-overhand loop knot which is used to attach the fly to the tippet. The fly is held within a loop at the end of the tippet. This reduces the 'lashing tail' effect which can occur with a conventional clinch or half-blood knot: A simple step but it may just make the difference between success and failure.

Paul Kenyon & Geoff Stephens, Fly Fishing Devon guides and instructors