Seminar

readings:

- Buss, (1995).

"Psychological sex

differences: Origins through sexual selection".

- The

Evolutionist "In

conversation with David Buss"

- Hewett (2002)

"Theory of Sexual

Selection: The Human Mind and the Peacock's Tail"

- Miller (1998)

"Sexual

Selection and the Mind" - interview with Miller in Edge magazine on May

26th 1998

- Kanazawa (2000).

"Scientific

discoveries as cultural displays: a further test of Miller's courtship

model". Evolution and Human Behavior, 21, 317-321, 2000.

|

- Miller

(2000) "The

Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature

- Chick (1998)

"What is Play For?

Sexual Selection and the Evolution of Play"

- Wilson

and Daly (1998)

"Lethal and nonlethal violence against wives and the evolutionary

psychology of male sexual proprietariness"

- Daly and

Wilson (1996) Evolutionary

psychology and marital conflict: the relevance of stepchildren"

- Daly

and Wilson (2001). "Risk-taking, Intrasexual

Competition, and Homicide".

|

The

status of sexual selection in

evolutionary psychology

|

View the PBS (2001)

Evolution video "Sex" to get an overview of

the factors involved in sexual selection

The

peacock fascinated Darwin:

How could natural selection alone have led to such an elaborate

plumage? Surely such an encumbrance would have jeopardized the bird's

survival?

He proposed that secondary

sexual characteristics of male animals evolved because

females preferred to mate with individuals that had those features.

Darwin wrote: "[Sexual

Selection] depends, not on a struggle for existence (i.e.

natural selection), but on a struggle between the males for

possession of the females; the result is not death to the unsuccessful

competitor, but few or no offspring." Charles Darwin, Origin of Species

(1859). Italics mine

View the PBS (2001)

"Tale of the Peacock" video featuring Petrie's work on

peacock tail feathers.

"Peahens often choose males for the quality of their trains -- the

quantity, size, and distribution of the colorful eyespots. Experiments

show that offspring of males with more eyespots are bigger at birth and

better at surviving in the wild than offspring of birds with fewer

eyespots."

In

this short video by Richard Dawkins

discusses how phenotypes and extended

phenotypes play an important role in

sexual selection

|

|

In

essence, sexual selection can

operate through two mechanisms:

- intersexual

selection: competition between members of the opposite

sex, e.g.

- females

and males choosing to mate with 'attractive' mates = 'selective mate

choice'

- 'male

sexual proprietariness' over females to protect against undetected

cuckoldry

- intrasexual

selection: competition between members of the same

sex e.g.

- males

competing with each other for access to females

|

In

these examples of intersexual selection

-selective mate choice

- a

female Satin Bower Bird inspects an avenue of twigs a foot or so apart

constructed by the male which has bright shiny blue feathers. The male

arranges blue objects in front of this avenue in order to attract a

mate. Notice the sexual dimorphism in this species - a brightly

coloured male bird courts a relatively dowdy female

- a

male suitor presents a woman with a token of his affection

|

|

|

Familiar

examples of males competing with each other for access to females -intrasexual

selection- include:

- stags

fighting during the rutting season

- the

creation and maintenance of 'dominance hierarchies'

- and

possibly, the tendency of young men to engage in risk taking and

inter-male aggression

|

|

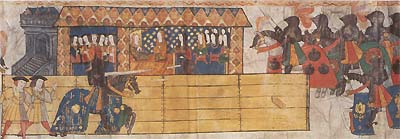

Frequently

inter- and intrasexual

selection behaviours are exquisitely intertwined.

This picture shows a modern re-enactment of medieval joust in which two

knights charge at each other on either side of a central barrier with

the aim of unhorsing their adversary with a lance in order to win their

lady's favour |

Inter- and intrasexual

selection? In medieval times knights swore to

uphold the values of courage and courtesy. Henry VII built a 'tiltyard' at Hampton Court where

he could joust with his courtiers as they recreated the chivalrous

exploits of medieval knights such as the legendary Sir Galahad - a

member of King Arthur's court. The tiltyard had a

special grandstand built in the middle for the queen and the ladies of

the court to get a better view. The

winner of the jousts was awarded a prize by the 'Queen of Beauty',

elected for the occasion from amongst the women present.

|

Parental

investment and sexual selection

Darwin's (1871) theory of

sexual selection was developed further by Trivers

(1972) who argued that

because of parental investment, the sex

that invests greater resources in

offspring will evolve to be the choosier sex in selecting a mate.

In contrast, the

sex that invests fewer resources in offspring will evolve to be more

competitive with its

own sex for access to the high-investing sex.

- Normally females are the

limiting sex and invest more in offspring than males.

- Because males tend to be in

excess, males tend to develop ornaments for attracting females or

engaging other males in contests.

(In

some species the roles of the

sexes may be reversed. See Goodenough et al, 2001 Chapter 14 for a very

good description

of sexual selection in animals).

Buss

(1999 p 41) provides a clear

description of why evolutionary psychologists have applied Trivers'

theory of parental

investment to human mating:

"The

differences between men and women in terms of the fitness costs of

making a poor mate choice are profound. An ancestral man who made a

poor choice when selecting a mate could have walked away without

incurring much loss. An ancestral woman who made a poor choice when

choosing a mate might risk becoming pregnant and perhaps having to

raise the child alone, without help."

| The BBC

website "More Science About Lonely Hearts" provides a useful

introductory overview of some topics researched

by evolutionary psychologists interested in sexual selection.

You can listen to Lynn Segal, Professor of

Psychology and Gender Studies at Birkbeck College, London and Ruth

Mace, Lecturer in the Department of Anthropology at University College

London debate the contribution of evolutionary psychology to

contemporary attitudes to marriage and parenting. (BBC

radio broadcast as part of "Woman's Hour" on Wednesday 8 August 2001)

|

Human mating systems:

monogamous females and polygamous males - a myth?

There

are several technical terms used to

describe mating systems that can cause confusion. This table may help

to clear things up

or create more bewilderment - let me know!

|

|

| Mating

system |

Male  |

Female |

| Monogamy |

mates with one female mates with one female |

mates with one male mates with one male |

| Polygamy: |

|

| Polygyny |

mates with more than one female mates with more than one female |

|

| Polyandry |

|

mates with more than one male mates with more than one male |

| Promiscuity |

mates with more than one female mates with more than one female |

mates with more than one male mates with more than one male |

|

Answer these questions after

you have studied the table:

- Which of the following

terms can be applied to male mating

systems?

- monogamy

- polygamy

- polygyny

- polyandry

- promiscuity

- Which of the terms can be

applied to female mating systems?

- Which of the terms can only

be applied to female mating systems?

- Which of the terms can only

be applied to male mating systems?

Male and female attitudes to multiple sexual

partners

| Evolutionary psychology

suggests that males have evolved an approach to mating that leads them

to seek multiple copulatory partners. This prediction - based on

Trivers' theory of parental investment - is consistent with the

following observations: |

|

- When

they are asked how many sexual partners they would like over a certain

period of time, men report that they would prefer more partners than

women,

- When

they are asked if they would agree to have sexual intercourse with an

attractive member of the opposite sex that they have known for varying

lengths of time, men and women express different likelihood's of

consent. Men reported that they would be slightly disinclined to have

intercourse with a woman they had known for just an hour. In contrast,

it is very unlikely that a woman would agree to intercourse after

knowing a man for this length of time. Source: Buss & Schmidt, Psychological

Review , 100, 204-232, 1993

|

|

|

|

|

| A note of caution; These

results are based on what men and women say about their desires and

preferences. People's replies to questions about what they think they

would do should be treated with caution. Researchers need to be wary of

demand characteristics influencing

participants' behaviour. Demand characteristics refer to participants

awareness of experimenters' goals or cultural expectations influencing

participants responses. See Mace (2000) for a discussion of this

confounding factor in evolutionary psychology research.

Another problem with

this type of prospective questionnaire in

which people say what they might do is

that it does not show that the behaviour has a measurable outcome on

reproductive fitness. Contrast this research technique with that

adopted by Pawlowski, Dunbar and Lipowicz (2000)

who examined the medical records of nearly 4,500 Polish men

aged between 25 and 60. They found that men who had fathered at least

one child were on average three centimetres (1.25 inches) taller than

men who had not fathered children. You can listen to a radio interview in which Dunbar

discusses various explanations for this result.

|

Short-term mating: "A

dance between the sexes?"

|

Although

the data (Buss & Schmidt, 1993) suggest that - compared to females - males

would like to mate with more partners over time, it does not

support the hypothesis that females are exclusively monogamous.

If you look carefully at the graph you will see that females would like

more than one partner in the next three years. This opens up the

possibility that a male may be cuckolded

and consequently waste his parental investment.

Bear this in mind as you progress through the readings on this page.

These factors may be relatedness to 'male sexual

proprietariness' which has been used to explain domestic

violence which

is discussed below. Although

the data (Buss & Schmidt, 1993) suggest that - compared to females - males

would like to mate with more partners over time, it does not

support the hypothesis that females are exclusively monogamous.

If you look carefully at the graph you will see that females would like

more than one partner in the next three years. This opens up the

possibility that a male may be cuckolded

and consequently waste his parental investment.

Bear this in mind as you progress through the readings on this page.

These factors may be relatedness to 'male sexual

proprietariness' which has been used to explain domestic

violence which

is discussed below.

Also examination of

these

results suggests that whereas:

- men

reported that they would be slightly disinclined to have intercourse

with a woman they had known for just an hour

- women

reported that they would be slightly disinclined to have intercourse

with a man they had known for three months

|

|

|

It is often claimed by

evolutionary psychologists that the cost of mating for men are

relatively slight. For example: "A man in human evolutionary history

could walk away from a casual coupling having lost only a few hours or

even a few minutes." (Buss, 1999, p102). But the interview-data

suggests that men may have to invest between three and six months in

courtship behaviours before they get the opportunity to mate. Whilst

this is much less than the nine months a woman devotes to pregnancy

plus the years of postnatal care, there is nevertheless a greater cost

to the male than is sometimes implied. The pre-mating costs for men

seem to have been discounted by evolutionary psychology.

It is often claimed by

evolutionary psychologists that the cost of mating for men are

relatively slight. For example: "A man in human evolutionary history

could walk away from a casual coupling having lost only a few hours or

even a few minutes." (Buss, 1999, p102). But the interview-data

suggests that men may have to invest between three and six months in

courtship behaviours before they get the opportunity to mate. Whilst

this is much less than the nine months a woman devotes to pregnancy

plus the years of postnatal care, there is nevertheless a greater cost

to the male than is sometimes implied. The pre-mating costs for men

seem to have been discounted by evolutionary psychology.

A small,

but significant, proportion of women in long-term relationships engage

in short-term matings (see figure). There must have been some selective

advantage for women to engage in short-term mating otherwise the

inclination to engage in this behaviour would never have had a

selection advantage for men. Buss (1999)

distinguishes between different types of explanations for female

short-term mating that have some experimental support in the human and

animal literature:

A small,

but significant, proportion of women in long-term relationships engage

in short-term matings (see figure). There must have been some selective

advantage for women to engage in short-term mating otherwise the

inclination to engage in this behaviour would never have had a

selection advantage for men. Buss (1999)

distinguishes between different types of explanations for female

short-term mating that have some experimental support in the human and

animal literature:

- acquisition

of resources from males

- acquisition

of a genetic resource e.g. the 'sexy son hypothesis' allows female to

bear a son with her genes who will attract females in the next

generation

- 'mate-switching':

dealing with a long-term partner who is resource-poor

To

sum up, I would suggest that the notion of monogamous

females and polygamous males is a myth. I would suggest

that there is more symmetry in the costs and benefits of short-term

mating for both sexes than hitherto acknowledged. It would advantage

the inclusive fitness of both males and females to engage in short-term

mating where the partner offers 'good biology', and any offspring would

be sufficiently resourced to ensure their survival to reproductive age.

Thus:

To

sum up, I would suggest that the notion of monogamous

females and polygamous males is a myth. I would suggest

that there is more symmetry in the costs and benefits of short-term

mating for both sexes than hitherto acknowledged. It would advantage

the inclusive fitness of both males and females to engage in short-term

mating where the partner offers 'good biology', and any offspring would

be sufficiently resourced to ensure their survival to reproductive age.

Thus:

- a man can increase his

inclusive fitness by engaging in short-term mating provided his mating

partner has 'good biology', and access to sufficient resources to

promote the survival and reproductive success of his

child.

- short-term mating can

increase an unpartnered woman's inclusive

fitness provided her mating partner has 'good biology', and she

has access to sufficient resources to promote the survival and

reproductive success of her child(ren).

- short-term mating can

increase a partnered woman's inclusive

fitness provided her mating partner has 'better biology' than her

long-term partner, and she does not loose access to sufficient

resources to promote the survival and reproductive success of her

child(ren).

This analysis suggests the

following hypotheses about the attitudes of genetic

relatives to short-term mating:

- a man's relatives can increase

their inclusive fitness by permitting / encouraging him to engage in short-term

mating particularly if the woman has access to

sufficient resources to promote the survival and reproductive success

of his child.

- a woman's relatives can increase

their inclusive fitness by permitting / encouraging her to engage in short-term

mating IF her mating

partner has 'good biology', and she has access to sufficient resources

to promote the survival and reproductive success of her child(ren).

- a woman's relatives can jeopardize

their inclusive fitness by permitting / encouraging her to engage in short-term

mating IF she does not

have access to sufficient resources to promote the survival and

reproductive success of her child(ren).

- To date most attention has

been focussed on hypothesis# 3 - the

control exerted over women's reproductive potential.

- Hypothesis# 1

reflects the 'double-standard' over men's sexual adventures

e.g. young men 'sowing wild oats'.

- Hypothesis# 2

is controversial but it seems to follow from the theory of inclusive

fitness. Certainly the literature focusses on measures taken to control

women's short-term mating. But under certain circumstances the benefits

of short-term mating might outweigh the costs, for example in

situations where there was a scarcity of long-term mating

opportunities, or where short-term mating could be kept secret from

long-term mates. As far as I know there is no experimental evidence for

or against hypothesis# 2.

Long-term

mating:"A battle between the sexes"?

In a groundbreaking study of long-term

mating strategies involving 10,047 participants from 33

countries Buss (1989)

showed that:

Males

prefer young, physically attractive,

and chaste mates.

Males

prefer young, physically attractive,

and chaste mates.  Females

place greater emphasis on the earning capacity

and ambitiousness-industriousness of

potential partners than men do.

Females

place greater emphasis on the earning capacity

and ambitiousness-industriousness of

potential partners than men do.

It is interesting that the

commentary elicited by this paper focussed on alternative explanations

involving economic powerlessness for the female preferences. The

findings on male desires did not provoke a spate of alternative

explanations based on cultural interpretations to challenge the

evolutionary explanation. Buss (1989) and Buss' responses to peer

commentaries are both available

online

According to conventional

evolutionary psychology (e.g. Buss, 1996)

these psychological differences between the sexes evolved

because the adaptive problems posed by

reproduction are different for

men and women. However, if we

examine the adaptive problems posed by long-term mating there

is remarkable symmetry between the

problems faced by the sexes:

- Both men and women

need to select mating partners with 'good biology',

i.e. to maximize fitness both sexes need to mate with fertile,

healthy partners who are likely to produce fertile, healthy

children.

- Both men and women

need to mate with partners who will remain 'faithful'

i.e.

- Women need to

select men able and willing to provide resources

(physical and behavioural) to promote the survival and reproductive

success of her child(ren),

AND

- Men need to

select women able and willing to provide resources

(physical and behavioural) to promote the survival and reproductive

success of his child(ren)

- this particular point is implied, but not stressed, by the

evolutionary psychologists I have read.

|

|

| 'Good

biology' or 'good genes'

Today's

paper carries a story headed "Technological advances may lead to

genetic apartheid, says scientist" (Akbar 2003).

"Sir

Paul Nurse, a Nobel prize-winner, who is the chief executive of cancer

research UK, predicts that in 20 years' time, it will be technically

possible to sequence the genome of each new baby." I read this and

wondered if a 'genetic identity card' might be an essential piece of

equipment for future generations steeped in evolutionary psychology

setting off to secure a 'one-night-stand'. But I am not convinced that

being armed with a person's genome would provide better clues to their

'good genes' than relying on the adaptations that have evolved to spot

fit short- and long-term partners.

I

have used the phrase 'good biology' in previous sections rather than

the more common expression 'good genes' after reading Keller (2000).

Keller's book is well worth reading if you are seeking answers to

questions such as "What does a gene do?" (see chapter 2) or "What are

genes for?" (see Conclusion). Genes are important for evolutionary

psychology because they permit the transmission of evolved adaptations

from parents and offspring (Buss 1999). However the term 'gene' is

borrowed from biology, and recent advances in molecular biology suggest

that the concept 'gene' is either very difficult to tie down, or has

now outlived its usefulness (Keller pp 66-72). Way back in 1953, Watson

and Crick's description of DNA's double helical structure lent support

to the idea that one gene controlled the production

of one enzyme. Abnormalities in a single gene are

known to give rise to severe disorders such as Huntington's disease or

phenylketonuria (PKU). This simple picture was captured by Francis

Crick who stated in 1957

"DNA makes RNA, RNA

makes protein, protein makes us." (See Keller., p 54).

But

this simple theory left open the question of what regulates the genes

to control the time, place and amount of protein production. All cells

have a nucleus with a full set of genes, but all cells do not produce

all the potential proteins that they are capable of manufacturing all

of the time. In 1959 Jacob and Monod suggested a distinction between 'regulator'

and 'structural' genes to deal with this problem. It

has been suggested that 97% of the human genome is involved in

regulating the 3% of genetic material that actually builds protein. The

discovery in 1977 that genes are fragmented along a chromosome and

interspersed with lengths of 'junk DNA' opened up the possibility that

the variety of protein constructed from DNA can vary during an

organism's life (see section on 'alternative splicing', Keller p 60).

Consequently, the notion of 'one gene - one protein' has been abandoned

to be replaced by 'one gene - many proteins'.

Perhaps the most unsettling message for evolutionary psychology from

molecular biology comes from recent 'knockout'

studies in which specific genes are disrupted in an intact animal. "In

many cases, knocking out a normal gene and replacing it with an

abnormal copy had no effect at all, even when the gene was thought to

be essential..." (Keller 2000, p 112). These results have added to the

belief that there is extensive redundancy built

into an animal's DNA.

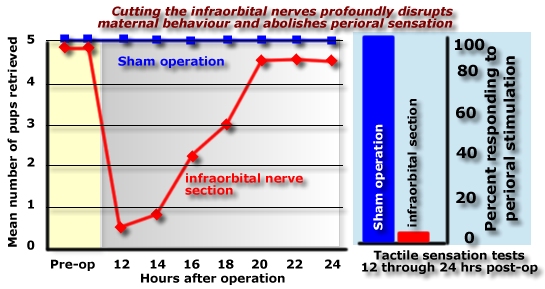

Redundancy

is a recurring familiar feature of biological systems. For example, our

own work (Kenyon et al.1983)

on retrieving behaviour in rats revealed that although cutting the

infraorbital branch of the trigeminal nerve - which transmits tactile

sensation from vibrissae to the brain - severely disrupts retrieving

behaviour for about 12 hours, this complex behaviour returned to normal

24 hours post-operatively even though tactile sensation was abolished.

Thus the mother rat was able to utilize some other (redundant?) system

to enable her to carry out this vital maternal behaviour.

|

Seminar

readings:

The paper by Buss,

D. M. (1995). "Psychological sex differences: Origins through sexual

selection". American Psychologist, 50, 164-168, available online provides a short

and clear explanation of sexual selection seen through the eyes of an

evolutionary psychologist. As you read the paper consider the following

points:

- Where, in broad terms, do

evolutionary psychologists predict we will find sex differences in

behaviour?

- Describe, in your own

words, the two forms of sexual selection.

- Briefly outline five

hypothesized sex differences in behaviour predicted by evolutionary

psychology.

- How to calculate Cohen's

'd' statistic is described by Thalheimer and Cook

( 2001-2003,). "How to calculate effect sizes from published research

articles: A simplified methodology" Work-Learning Research, Somerville,

Massachusetts, USA, available online

- Make a list of behaviours

which exhibit large and small

effect-size differences between the sexes.

Read The Evolutionist

"In conversation with David Buss" which is available online and consider the

following points:

- What are the differences

between male and female short- and long-term mating strategies?

- What does Buss mean when he

remarks that "Some people have conflated the causal process that

produces adaptation with the nature of adaptation itself."?

- Why has there been a

relatively slow take up of evolutionary ideas within psychology?

- Can you give evidence to

support the jibe that "if a social scientist witnesses something that

looks like a duck, walks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then he

says it's a social construction of a duck."?

- Can evolutionary psychology

explain the sexual revolution that occurred in the 'swinging 60s'?

- What is a 'New Man' and can

it be explained in terms of evolutionary psychology?

- Can 'lad' and 'ladette'

culture be explained in terms of evolutionary psychology?

Read Hewett

(2002) "Theory of Sexual Selection: The Human Mind and the Peacock's

Tail" (online article) and consider the

following points:

- Explain

Fisher's view that the peacock's tail is the product of 'runaway'

sexual selection.

- Zahavi

views the peacock's tail as a handicap. How then could it evolve?

- What

is the 'lek paradox', and how can it be resolved?

- Why

did the human brain evolve to be so big?

|

Read the interview

(Sexual Selection and the Mind) with Miller in Edge

magazine on May 26th 1998 (available online). This article

provides an accessible introduction to Miller's view of the role of sexual

selection in the evolution of human behaviour. As you read

the article consider the following points: |

|

- How

is Miller's approach to explaining the evolution of human behaviour,

different from mainstream evolutionary psychology?

- What

behaviours does Miller focus on? Can these be explained by evolutionary

psychology?

- Explain

the terms: mate choice, natural selection, sexual selection, human

'universals', tabula rasa,

- Can

evolutionary psychology explain variation in intelligence? If not, why

not?

- Are

there important differences between male and female psychologies?

- Does

pulverizing the tabula rasa take pressure off

parents trying to raise children?

- To

what extent is the concept of sexual selection central to the

psychology you have studied as an undergraduate?

Most of

you will have engaged in courtship behaviour at some time in your

lives. How much have you learnt about this behaviour as a psychology

student? Look up 'courtship' in the index of several psychology

textbooks. How much would you learn about this behaviour in humans

if you read psychology texts? Look up 'cerebellum' in the index of

several psychology textbooks. How much would you learn about this

structure if you read psychology texts?

Most of

you will have engaged in courtship behaviour at some time in your

lives. How much have you learnt about this behaviour as a psychology

student? Look up 'courtship' in the index of several psychology

textbooks. How much would you learn about this behaviour in humans

if you read psychology texts? Look up 'cerebellum' in the index of

several psychology textbooks. How much would you learn about this

structure if you read psychology texts?

- What

factors are thought to influence mate choice? See also Buss (1999)

- Why

do we speak?

- How

would you test the hypothesis that vocabulary size has been shaped by

sexual selection?

- Why

do we make, and enjoy, music?

- Should

scientists studying human behaviour be worried about the implications

and applications of their findings?

Read Kanazawa

"Scientific discoveries as cultural displays: a further test of

Miller's courtship model". Evolution and Human Behavior, 21, 317-321,

2000. (Available from library offprints collection) which describes an

empirical study based on Miller's theory. As you read this paper

consider the following points:

Read Kanazawa

"Scientific discoveries as cultural displays: a further test of

Miller's courtship model". Evolution and Human Behavior, 21, 317-321,

2000. (Available from library offprints collection) which describes an

empirical study based on Miller's theory. As you read this paper

consider the following points:

- Outline

Miller's courtship model.

- What

were the hypotheses in Kanazawa's study?

- Do

you think that "men compete for their mates much more fiercely than

women"? What are the implications of your answer for the study of

sexual selection in human behaviour?

- What

were the independent and dependent variables in Kanazawa's study?

|

Here are rough graphs

showing some of the results presented by Kanazawa. You can use this

'slide projector' to display the age distributions of peak scientific

achievement for:

- married or

- unmarried

male

scientists

Kanazawa

reported a significant difference in the mean age between the married

and unmarried scientists. What statistical test would you carry out to

determine if the distributions of the age of peak scientific

performance are significantly different between married and unmarried

scientists?

|

- Can

you think of alternative explanations for the relatively few female

scientists in Kanazawa's sample?

- Can

you think of alternative explanations for the sustained productivity of

unmarried male scientists?

- What

advice would you give to a recruitment panel wanting to improve the

research output of a university department?

Read Miller

(2000) "The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of

Human Nature", Doubleday/Heinemann. A précis of the book is available online. Bear the

following points in mind as you read:

Read Miller

(2000) "The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of

Human Nature", Doubleday/Heinemann. A précis of the book is available online. Bear the

following points in mind as you read:

- What

evidence is there to suggest that kin selection plays a major role in

shaping human behaviour? Can you recognize your blood relatives before

you are introduced to them? Who is your 'cousin once removed'? Are they

blood relatives? Are all your uncles and aunts blood relatives? What is

your mother's sister's husband called? Is he a blood relative? What is

your mother's brother called? Is he a blood relative? Why are they both

called uncle? Are you aware of different expectations of the care that

you can expect from these individuals? Why is our language so clumsy

when describing our blood ties to relatives, but so precise when

describing where players are located on a cricket pitch, or football

field?

- Is

the human brain a sexually selected ornament?

- Briefly

outline the history of the concept of sexual selection.

- Describe

Zahavi's 'handicap principle'.

- Why

has evolutionary psychology apparently ignored sexually selected mental

traits?

- Explain

the terms high and low heritability. What is their significance?

- How

would you test the hypothesis that sexual selection plays a role in

modern human mate choice?

- Is

psychology too prudish?

- Explain

the terms: runaway sexual selection; positive feedback process.

- What

are 'sexual ornaments'? Are they sexually dimorphic?

- Is

Miller's Courtship Hypothesis sexist?

- Explain

the term 'mutual mate choice'. Does it rescue Miller's hypothesis from

the charge of sexism?

- Why

is the human brain a good index of 'fitness'?

- What

is the 'good genes' model of sexual selection?

- Does

serial monogamy preserve genetic variation in fitness indicators?

- Explain,

with examples, the term 'super-stimulus'.

- Explain

the term 'fitness matching'.

- Does

fitness matching explain the lack of sexual dimorphism in human brain

size and courtship behaviours?

- Explain

the term 'extended phenotype'.

Here is a short video by Richard Dawkins

that explains the place of extended phenotypes within evolutionary

theory

Here is a short video by Richard Dawkins

that explains the place of extended phenotypes within evolutionary

theory

- What

are the limitations of kin selection and reciprocal altruism as

explanations of human behaviour?

- Why

do men hunt? see also Barrett et al.

(2002).

- What is the function of

language in Miller's

Courtship Hypothesis?

Read Chick (1998) "What

is Play For? Sexual Selection and the Evolution of Play", which is available online.

Bear in

mind Burghardt's comment (cited in Chick):

"In

most areas of behavior, the functional approach has yielded great

rewards rather quickly once adaptive explanations have been carefully

stated and explored"

as you

consider the following points:

- Distinguish

between 'ultimate' and 'proximate' explanations of behaviour.

- Describe

the features of plants and animals that support natural selection.

- Distinguish

between 'natural' and 'sexual' selection.

- Write

brief notes on the evidence which supports Chick's statements about

play:

- Play

is characteristic of vertebrates

- Play

is characteristic of organisms with relatively long life spans

- Play

seems to be correlated with the relative size and complexity of the

neocortex

- Play

is most typical of young animals and peaks during periods of maximal

cortical development

- Play

commonly involves behaviour patterns adapted from their usual contexts

- play

disappears under stress

- Play

typically involves the communication, "This is play".

- Species

that maintain significant levels of playfulness into adulthood

typically also retain other neonatal characteristics.

- Play

is fun.

- Is

play an 'adaption' or an 'exaptation'?

- Has

play evolved through sexual selection?

Domestic violence

Cuckold:

a man whose wife has sex or becomes impregnated by a man other than

himself . Here is a 19th century French print

entitled "The celebration of the Order of Cuckoldry before the throne

of her majesty, Infidelity" Notice the repentant husband whose wife is

pointing to the antlers on her own head!

Wilson and Day (1998a)

have postulated a 'male sexual proprietariness'

module that is adapted to protect human male reproductive fitness

against undetected cuckoldry

i.e. a set of behaviours to prevent a man's partner being impregnated

by another man. They suggest that because of paternal

uncertainty, and the cost of paternal

investment, male fitness will be reduced if a male is

cuckolded. Wilson and Daly postulate that male sexual proprietariness

is an adaptation that has evolved through

natural selection to overcome this risk.

Wilson and Day (1998a)

have postulated a 'male sexual proprietariness'

module that is adapted to protect human male reproductive fitness

against undetected cuckoldry

i.e. a set of behaviours to prevent a man's partner being impregnated

by another man. They suggest that because of paternal

uncertainty, and the cost of paternal

investment, male fitness will be reduced if a male is

cuckolded. Wilson and Daly postulate that male sexual proprietariness

is an adaptation that has evolved through

natural selection to overcome this risk.

It is very important to

stress that this is a classic example of the type of proposal that can

generate considerable controversy if the suggestion that something "is"

is mistakenly taken to mean that therefore it is "natural" or "ought"

to be. No evolutionary psychologist is suggesting that male sexual

proprietariness is a "good thing". (Here is a discussion of common

misconceptions about evolutionary psychology).

It is very important to

stress that this is a classic example of the type of proposal that can

generate considerable controversy if the suggestion that something "is"

is mistakenly taken to mean that therefore it is "natural" or "ought"

to be. No evolutionary psychologist is suggesting that male sexual

proprietariness is a "good thing". (Here is a discussion of common

misconceptions about evolutionary psychology).

At the risk of stating the

blindingly obvious it is worth pointing out that women are not

monogamous. The phrase "till death do us part" is all-to-often a

romantic illusion. When they are asked how

many sexual partners they would like over a certain period of

time, women responded

that they would like more than one partner in the next year (see above). Of course this is an

average figure for the group of women interviewed; some will prefer to

remain monogamous, others may anticipate more than two partners.

Nevertheless, cuckoldry is a real potential risk to male fitness. Both

men and women can experience strong emotions if they see or believe

their partner is, or has, formed a romantic relationship within

another. Although Wilson and Daly's work focusses on male sexual

proprietariness evolutionary psychology predicts a comparable module in

females.

Read Wilson and Daly

(1998a) "Sexual rivalry and sexual conflict: recurring themes in fatal

conflicts". Theoretical Criminology.vol. 2(3):291-310, available online and consider the

following points:

- page 296 contains a brief

description of an experiment by Buss et al (1992) in which

undergraduates were asked to indicate which of two dilemmas they

considered more serious:

- their partners

forming a deep emotional attachment to another person

- their partners enjoying

passionate sexual intercourse with another person.

- the results show a sex

difference with 60% of men being more upset by the second option

whereas 83% of women choose option# 1

This

was a 'forced-choice' dilemma. Participants had to choose one option

over the other. Why do you think 40% of men chose option# 1.

In the light of the results reported by Buss & Schmidt (1993):

In the light of the results reported by Buss & Schmidt (1993):

- Which

of the two female behaviours in the scenario is more likely to endanger

male reproductive fitness?

- Which

male reaction is more likely to promote male reproductive fitness?

Male sexual

proprietariness consists of a set of controlling behaviours

of increasing severity that can culminate in 'uxoricide' i.e.

murder of a female by her male partner. Wilson and Daly have focussed

on uxoricide because it is a clear behavioural endpoint. Nevertheless

there is a spectrum of preceding behaviours that they interpret as

being male attempts to control female reproductive effort.

Male sexual

proprietariness consists of a set of controlling behaviours

of increasing severity that can culminate in 'uxoricide' i.e.

murder of a female by her male partner. Wilson and Daly have focussed

on uxoricide because it is a clear behavioural endpoint. Nevertheless

there is a spectrum of preceding behaviours that they interpret as

being male attempts to control female reproductive effort.

The

Independent newspaper reported recently that "According to the Home

Office, there are 635,000 incidents of domestic violence a year. One in

four women will be abused by their husbands or boyfriends during their

lifetime and, on average, two women a week are killed by a current or

former partner." (Goodchild, 2003).

As you read the evidence in

the next section, it may help to organize the material into a table

along the lines shown here to identify 'risk factors'

that may increase a woman's chance of

becoming the victim of domestic violence, and a corresponding list of

factors that may reduce her risk. Here is

a copy of the table that you can

print out

| Risk

factor for domestic violence |

Conditions

that increase risk |

Conditions

that decrease risk |

Reference

and caveats |

| Age |

risk higher in women

15-34 |

risk declines after 35 |

see Wilson &

Daly (1998) Figure 8.2. Caveat: may be confounded with man's age |

| Type of

union |

unmarried |

married |

see Wilson &

Daly (1998) |

| Add factors you

identify in this column and ... |

fill

in these cells as you progress through the readings |

Read Wilson and Daly

(1998) "Lethal and nonlethal violence against wives and the

evolutionary psychology of male sexual proprietariness" available online. and consider the

following points:

- What is uxoricide?

- From an evolutionary

perspective, why should men act violently towards their partners?

- Explain what it means to

suggest that uxoricide is an epiphenomena of evolved male psychology.

- Are lethal and nonlethal

violence against female partners on a continuum?

- What are the roles of

adultery and jealousy in violence against female partners?

- Explain the difference

between jealousy and 'sexual proprietariness'?

- Describe the legal

consequences of cuckoldry across cultures.

- Do you think warnings of

possible male partner adverse reactions to rape should be included in

the counselling given to rape victims?

Examine these data from Wilson

and Daly (1998) table 8.1 and 8.2

| Percentage

of women who have experienced increasing levels of violence agreeing to

statements about the behaviour of their male partner. (Redrawn

from Wilson and Daly 1998, table 8.1) |

| |

Violence |

None

(n=7060) |

"Nonserious"

(n=1039) |

"Serious"

(n=286) |

| "He is jealous and does not’t want you

to talk to other men" |

3.5 |

13 |

39.3 |

| "He tries to limit your contact with friends or

family" |

2 |

11.1 |

35 |

| "He insists on knowing who you are with and where

you are at all times" |

7.4 |

23.5 |

40.4 |

| "He calls you names to put you down or make you

feel bad" |

2.9 |

22.3 |

48 |

| "He prevents you from knowing about or having

access to the family income, even if you ask" |

1.2 |

4.6 |

15.3 |

| Autonomy-limiting Index (Average number of items

affirmed by women) |

0.17 |

0.74 |

1.78 |

|

|

| To

what extent do you think the 'Autonomy-limiting Index' might provide

the basis for creating a risk index to assess the dangers faced by

women in abusive relationships? |

Examine

this figure from Wilson and Daly (1998). On the basis of this evidence,

what advice would you offer a battered wife contemplating leaving her

partner?

Examine

this figure from Wilson and Daly (1998). On the basis of this evidence,

what advice would you offer a battered wife contemplating leaving her

partner? - Explain, in evolutionary

terms, why undetected cuckoldry reduces male fitness.

- What are the limitations

associated with using undergraduates as participants in studies of

human sexuality?

- Wilson and Daly make

several predictions of 'risk factors' that may increase male sexual

violence:

- degree of local

competition between men for access to women;

- poor economic and

health prospects

- size of age cohort

- Do you think Wilson

& Daly would argue that school education programmes alone

would reduce male sexual proprietariness?

- Explain the term, and the

cultural, behavioural and physiological mechanisms involved in,

'mate-guarding'.

- What are the benefits of

marriage to men and women?

This

figure is taken from Daly and Wilson

(1996) "Evolutionary psychology and marital conflict: the relevance of

stepchildren", available online. Are a woman's age, and the the presence of

stepchildren in the home risk factors for domestic violence?

This

figure is taken from Daly and Wilson

(1996) "Evolutionary psychology and marital conflict: the relevance of

stepchildren", available online. Are a woman's age, and the the presence of

stepchildren in the home risk factors for domestic violence?

Evolutionary

psychology and artificial insemination by donor

According

to evolutionary psychology some aspects of men's behaviour are directed

towards controlling female reproductive behaviour. For example, 'male

sexual proprietariness' is seen as part of an adaptation to reduce the

risk to male reproductive fitness posed by cuckoldry which reduces the

returns from paternal investment.

Artificial

insemination is one of the oldest and simplest treatments for human

infertility. There are two fundamentally different types of artificial insemination:

- In

artificial insemination with husband

sperm, the semen containing the sperm is obtained from the woman's male

partner.

- In

artificial insemination with donor sperm,

the semen containing the sperm is obtained from a volunteer who is not

known by the patient.

A man

who agrees that his partner be artificially inseminated with donor

sperm is agreeing to provide resources for a child that does not share

his genes. In contrast, a man who agrees that his partner be

artificially inseminated with his sperm

is agreeing to provide resources for a child that does share his genes.

Does this decision affect his behaviour towards his partner and child?

Evolutionary psychology would predict that couples who have children

through artificial insemination with husband

sperm would be less likely to experience family problems than couples

who have children through artificial insemination with donor

sperm.

Intrasexual

selection

Read

Daly and Wilson (2001).

"Risk-taking, Intrasexual Competition, and Homicide". Nebraska

Symposium on Motivation, 47:1-36. available online and

consider the following points:

- Explain

the meaning of the terms 'risk proneness / seeking', 'risk aversion'

and 'loss' in decision making research.

- Explain,

with examples, the conditions under which men might choose higher-risk

options. You should add to your answer as you proceed through the paper.

- Why

might a normally risk-averse animal switch to high risk behaviour?

- Explain

in your own words Daly and Wilson's comment that "...sex differences in

the variance of reproductive success are widely

considered indicative of sex differences in intrasexual

competition." my underlining (Daly and Wilson, 2001, p. 7-8)

- Make

brief notes to support the claim that men are polygynous.

- To

what extent are men less sensitive to risk than women ?

- What

is the relationship between gender, risk taking behaviour and status?

- If

risk taking is an adaptation, under what conditions would you expect a

man's attitude to risk to change as he gets older?

- Is

it legitimate to use homicide as a marker for male risk taking

behaviour?

- Is

male-on-male homicide simply the unfolding of a 'biological

predisposition' to violence in young men? Or is it an adaptation

sensitive to unconsciously perceived environmental conditions? If so,

what are these environmental conditions? You should add to your answer

as you proceed through the paper.

- Are

people's perceptions about future prospects 'rational' when viewed from

an evolutionary perspective?

- What

are the implications of Daly and Wilson's paper for social policy?

|

|

Building links between evolutionary psychology

and psychobiology

Psychobiology

is a broad term and somewhat loose term that groups together a wide

range of disciplines studied by psychologists and biologists.

Psychobiologists are interested in studying the biological bases of

behaviour. The term psychobiology covers a wide range of

sub-disciplines within psychology and biology including: physiological

psychology, psychopharmacology, developmental psychobiology, ethology,

neuroethology, animal behaviour, psychoneuroendocrinology, behavioural

and cognitive neuroscience, and psychoneuroimmunology.

Evolutionary

psychology focusses on why behaviours evolved in

particular ways.

For example, according to evolutionary psychologists, in species where

one sex makes a higher parental investment than the other - the high

investing sex - is a resource for which the opposite sex competes.

In the

next section we will examine some material that suggests that

psychobiology may be able to shed some light on sex differences in

risk-taking behaviours.

Aggression and sexual selection

In

humans, females make a higher parental investment

than do males. Males compete with each other for access to females.

Males use their dominance and resources to deter rivals and attract

females. Evolutionary psychologists argue that the higher rate of

aggression in men shows the crucial importance of status to male

reproductive success.

However

women can, and do show, aggressive behavious (see Campbell,

1999).

Females compete with each other, and men, for resources that will

enable them to successfully raise their children.

Sex differences in human

aggression

|

Over

80% of homicides are committed by men.

Most of

the victims are also men. The most common cause of homicide is due to

the escalation of a relatively trivial disagreement over status that

starts with words and escalates into lethal violence. It seems that men

resort to violence to protect or gain status and honour.

This

sex difference is found across all cultures. Criminal violence is most

likely between the ages of 14 and 24. (see Campbell, 1999).

Some

psychologists have argued that boys are trained

to be aggressive and girls learn to be passive. However, Dyson-Hudson

(1995) found that: " 'low-conflict societies' with affectionate

socialization and aversion to inter-personal confrontation (e.g. Inuit,

!Kung Bushmen, Gebusi of lowland New Guinea) have high rates of violent

death. In contrast, Turkana pastoralists (East Africa) are taught to

fight as children; and most men reported having participated in inter-

personal fights intended to cause injury, having engaged in

recreational within-group fighting mimicking warfare, and having taken

part in raids on the neighboring Pokot. Yet demographic data indicate

that within- group homicide rates among the 'violent' Turkana are lower

than those reported for the 'low-conflict' societies.

It

may be that Turkana rules which require bystander intervention and

adjudication by elders, are effective in preventing within-group

aggression and violence from escalating into lethal fights. "

|

Male

aggression

Richard Wrangham (Wright

and Wrangham, 1998) presents an interesting analysis of male violence

in terms of evolutionary psychology. He argues that:

Richard Wrangham (Wright

and Wrangham, 1998) presents an interesting analysis of male violence

in terms of evolutionary psychology. He argues that:

- Chimpanzees and

humans are the only species in which groups of males hunt and kill

members of their own species. In the Scientific

American Frontiers video (2001) "Chimps

Observed", Goodall describes her work, and discusses the

implications of lethal intraspecific aggression in chimps

- Therefore murder is not a

unique 'culturally determined' human

behaviour

- Chimpanzees patrol their

territorial borders in a group and will kill an isolated

animal from a neighbouring group. Under these circumstances there is little

risk that the aggressor will be seriously injured

whereas the victim will either be killed, or seriously harmed.

- Some forms of human

violence involve an accurate assessment of the risk of injury (e.g. the

Mafia are reputed to wait for a numerical advantage before they attack

their victim).

However warfare

is a uniquely human behaviour. In a battle both sides will

suffer casualties regardless of who finally wins. Consequently battles

involve a failure to assess the true costs of combat by both sides.

Wrangham suggests that this failure is due to 'positive

illusions' by each set of combatants that they will

emerge victorious

However warfare

is a uniquely human behaviour. In a battle both sides will

suffer casualties regardless of who finally wins. Consequently battles

involve a failure to assess the true costs of combat by both sides.

Wrangham suggests that this failure is due to 'positive

illusions' by each set of combatants that they will

emerge victorious

Female

aggression

Until recently, relatively little attention was

focussed on female aggression. Campbell (1999) argues that

".. lower rates of aggression by women reflect

not just the absence of masculine risk-taking but are part of a

positive female adaptation driven by the critical importance of the

mother's survival for her own reproductive success."

|

Campbell

reviews evidence that:

- women show

greater fear of physical harm compared to men.

For example:

- women show more

fear of open spaces, dogs, snakes, insects, and rodents than men

- women

are less likely to engage in hazardous sports, dangerous driving,

military combat, and drug abuse, than men

- women are more

afraid of being victims of crime involving aggression, and are more

likely to visit a doctor to seek advice on preventative care, than men

- women commit fewer

violent crimes than men (see Campbell et al, 2001)

- women show less

concern for status compared to men

- greater adoption of

dispute resolution strategies that involve a low risk of physical harm

by women compared to men

- female 'maternal

aggression' to defend their offspring; paternal aggression is rarer

- female menopause - an

infertile period after the birth of the last child will ensure its

survival

This is a picture of Phoolan Devi, (Seema Biswas)

so-called "Bandit Queen of India", she led a gang who roamed

north central India during the late 1970s and early 1980s; she became a

folk hero after taking bloody revenge against men who raped her.

|

These

stills are taken from the French film 'Baise Moi" which was banned in

several countries. The film deals with a young woman who has been

raped, and an accomplice, who embark on a spree of violence and

promiscuous sex. It is interesting to reflect on this film's treatment

by censors in the light of Campbell's argument that

"...Women's aggression

has been viewed as a gender-incongruent aberration or dismissed as

evidence of irrationality. These cultural interpretations have

"enhanced" evolutionarily based sex differences by a process of

imposition which stigmatises the expression of aggression by females

and causes women to offer exculpatory (rather than justificatory)

accounts of their own aggression."

|

|

|

Neurotransmitters

& Aggression

Serotonin and

aggression- animal studies

Increased serotonergic

activity tends to reduce aggressive behaviour in rodents.

- Isolation-induced,

resident-intruder and maternal aggression reduced by 5-HT agonist drugs

(agonists increase activity at neurotransmitter receptor sites )

- mutant

mice lacking the 5-HT 1B receptor gene show decreased attack latency,

and an increased number of attacks in the isolation-induced aggression

model (see Fig. 9.24 Feldman et al (1997)

Adapted

from Fig 11.18 Carlson (1998)

|

Higley et al (1996)

studied free-ranging rhesus monkeys living on an island. Used

behavioural observations and sampled CSF (cerebro spinal fluid) to

measure 5-HIAA levels (5-HIAA is a breakdown product of 5-HT - the more

5-HIAA the greater 5-HT release).

- found

negative correlation between 5-HIAA and aggression. No relationship

between aggression and NA or DA metabolites.

- Low

5-HIAA associated with high risk-taking behaviour -aggression towards

older larger animals, took long leaps from tree to tree. Many died as a

result of attacks from mature males.

- low

5-HT turnover may reflect low impulse control rather

than increased aggression per se

|

"Dominance and

aggression are not synonymous." (Carlson,1998)

. Serotonin levels are

effected by dominance rank. Raleigh et al, (1984)

- 5-HT level is higher in

dominant than subordinate male vervet monkeys

- Removing

dominant male changes dominance hierarchy within remaining animals.

- New

dominant male shows increase in his 5-HT level.

- Restoring

previously dominant male provokes restores original 5-HT levels.

Redrawn

from Fig 9.25 Feldman (1997)

|

Raleigh et al (1991) investigated effects of serotonergic drugs on

dominance and aggression. Used 12 groups of vervet monkeys. Temporarily

removed dominant male from each group. The two remaining subordinate

monkeys were treated with

- serotonergic

drug

- control

(placebo)

The

serotonergic drugs used were

- 5-HT

agonists (tryptophan or fluoxetine)

which increase 5-HT activity

- 5-HT

antagonists (cyproheptadine or

fenfluramine) which decrease 5-HT activity (chronic treatment with

fenfluramine depletes 5-HT levels )

Used

a crossover design so that each monkey received

agonist and antagonist treatments.

Results:

- monkeys

given agonist drugs became dominant

- monkeys

given antagonist drugs became subordinate

- monkeys

given agonist drugs initiated fewer aggressive

events

- monkeys

given antagonist drugs initiated more aggressive

events

Note

that because a cross over design was used the same animal could be

dominant or subordinate depending on what type of serotinergic drug

they received.

|

Serotonin and human aggression

|

- Reduced

concentrations of 5-HT and 5-HIAA in brains of suicide victims.

- Maybe

suicide and violence towards other people represent the same underlying

aggressive tendency

- Low

5-HIAA levels in brains of suicides who used violent means to end their

own lives (using guns or jumping from heights rather than by ingesting

pills or taking a poison)

- in

normal adults there is a negative correlation between 5-HIAA level and

'urge to act out hostility' subscale of the Hostility and Direction of

Hostility Questionnaire

- in

psychiatric patients there is a negative correlation between 5-HIAA

level and psychological measures of aggression

- low

5-HIAA linked to impulsive, antisocial aggressiveness

- low

5-HIAA reported in children with disruptive behaviour

|

Author

Paul

Kenyon

References

and online resources

- Anon

(1998). "Sexual Selection and the Mind: A talk with Geoffrey Miller,

Edge, 41, May 26th 1998, available

online

- Akbar (2003) "Technological advances may

lead to genetic apartheid, says scientist". The Independent newspaper

4th March p 7

- Barrett, et al. (2002).

Human

Evolutionary Psychology , Palgrave.

- BBC

(2001). "Woman's Hour"- Mace and Segal debate evolutionary psychology's

approach to marriage and parenting. Broadcast on Wednesday 8

August 2001

- BBC

(2002). Human Instinct programme support materials: "More

Science About Lonely Hearts" available online

- BBC

(2003) Hitting Home - Domestic violence web site

- Buss

list of research papers available online

- Buss,

D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary

hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral & Brain Sciences,

12, 1-49. available

online

- Buss,

D. M. (1995). "Psychological sex differences: Origins through sexual

selection". American Psychologist, 50, 164-168, available online

- Buss

(1996) "Sexual Conflict: Evolutionary Insights into Feminism and the

'Battle of the Sexes'", (In Buss and Malamuth "Sex, Power, Conflict:

Evolutionary and Feminist Perspectives", Oxford University Press),

- Buss, DM. (1999). Evolutionary

Psychology: The New Science of the Mind. Allyn and Bacon, Boston.

- Campbell

(1999). Staying alive: Evolution, culture and women's intra-sexual

aggression. Behavioural and Brain Sciences, 22, 203-252, available online

- Cheshire

Constabulary (ND) "Domestic violence" web page

- Chick

(1998) "What is Play For? sexual selection and the Evolution of Play"

Keynote address presented at the annual meeting of The Association for

the Study of Play, St. Petersburg, FL, February 1998, available online,

- Daly

and Wilson: list of research papers available online in pdf format

- Daly

and Wilson (1996) Evolutionary

psychology and marital conflict: the relevance of stepchildren.

Pp. 9-28 in DM Buss & N Malamuth, eds., Sex, power, conflict:

feminist and evolutionary perspectives. New York: Oxford University

Press.

- Daly

and Wilson (2001). "Risk-taking,

Intrasexual Competition, and Homicide". Nebraska Symposium on

Motivation, 47:1-36. available online

- Daly,

Wiseman, and Wilson (1997) "Women

with children sired by previous partners incur excess risk of

uxoricide". Homicide Studies 1: 61-71.

- Darwin (1859). Origin

of Species . Available online

- Darwin

(1871). The descent of man and selection in relation to sex,

available online GET URL

- Dyson-Hudson

(1995), Paper presented at the Human Behavior and Evolution Conference,

Santa Barbara, June 1995

- The Evolutionist

"In conversation with David Buss" available online

- Feldman et al, (1997).

Principles of Neuropsychopharmacology, Sinauer, Sunderland, MA., 1997

- Goodchild

(2003). "Lessons on viloence at home for 10-year-olds", The Independent

newspaper, 16th February, 2003 p. 13.

- Goodenough,

McGuire and Wallace (2001) Perspectives on Animal Behavior,

2nd Edition, Wiley, New York.

- Hewett

(2002) Theory of Sexual Selection: The Human Mind and the Peacock's

Tail online article

- Higley et al, (1996). Archives

of General Psychiatry , 53, 537-543.

- Kanazawa

(2000) Scientific discoveries as cultural displays: a further test of

Miller's courtship model. Evolution and Human Behavior, 21, 317-321,

2000. (Available from University of Plymouth, library offprints

collection)

- Keller

(2000). The Century of the Gene, Harvard University Press: Cambridge

Mass.

- Kenyon, Cronin and

Keeble (1983).Behavioral Neuroscience, 97, 255-269.

- Kruttschnitt,

C. (1994) Gender and interpersonal violence. In A. Reiss

and J. Roth (Eds.) Understanding and Preventing Violence

Volume 3. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

- Mace (2000). Evolutionary

ecology of human life history, Animal Behaviour ,

59, 1-10.

- Miller

(2000) "The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of

Human Nature", Doubleday/Heinemann, a precis is available online

- Pawlowski,

Dunbar and Lipowicz (2000). Evolutionary fitness: Tall

men have more reproductive success. Nature 403, 156 (2000) abstract available online. Listen

to a radio interview in whch Dunbar

discusses this result.

- PBS

(2001) "Tale of the Peacock". Video featuring Petrie's work on

peacock tail feathers.

"Peahens often choose males for the quality of their trains -- the

quantity, size, and distribution of the colorful eyespots. Experiments

show that offspring of males with more eyespots are bigger at birth and

better at surviving in the wild than offspring of birds with fewer

eyespots."

- PBS

(2001) Evolution "Sex" video available online

- Raleigh et al,

(1984). Archives of General Psychiatry , 41,

405-410.

- Raleigh et al,

(1991). Brain Research , 559, 181-190 .

- Trivers

(1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In Campbell (Ed).

Sexual selection and the descent of man:1971-1971 (pp136-179).

Chicago:Aldine.

- Thalheimer

and Cook ( 2001-2003,). "How to calculate effect sizes

from published research articles: A simplified methodology"

Work-Learning Research, Somerville, Massachusetts, USA, avalable online

- Wilson and

Daly (1998) Lethal

and nonlethal violence against wives and the evolutionary psychology of

male sexual proprietariness. Pp. 199-230, In RE Dobash

& RP Dobash, eds., Violence Against Women: International and

Cross-disciplinary Perspectives. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

- Wilson and Daly (1998a) Sexual

rivalry and sexual conflict: recurring themes in fatal conflicts.

Theoretical Criminology.vol. 2(3):291-310.

- Wright and

Wrangham, (1998) Morals, Demonic Males and Evolutionary

Psychology. In Information and Biological Revolutions: Global

Governance Challenges--Summary of a Study Group by Francis Fukuyama

Caroline S. Wagner. This project was conducted in RAND's Science and

Technology Policy Institute. Available online

Although

the data (Buss & Schmidt, 1993) suggest that - compared to females - males

would like to mate with more partners over time, it does not

support the hypothesis that females are exclusively monogamous.

If you look carefully at the graph you will see that females would like

more than one partner in the next three years. This opens up the

possibility that a male may be cuckolded

and consequently waste his parental investment.

Bear this in mind as you progress through the readings on this page.

These factors may be relatedness to 'male sexual

proprietariness' which has been used to explain

Although

the data (Buss & Schmidt, 1993) suggest that - compared to females - males

would like to mate with more partners over time, it does not

support the hypothesis that females are exclusively monogamous.

If you look carefully at the graph you will see that females would like

more than one partner in the next three years. This opens up the

possibility that a male may be cuckolded

and consequently waste his parental investment.

Bear this in mind as you progress through the readings on this page.

These factors may be relatedness to 'male sexual

proprietariness' which has been used to explain  It is often claimed by

evolutionary psychologists that the cost of mating for men are

relatively slight. For example: "A man in human evolutionary history

could walk away from a casual coupling having lost only a few hours or

even a few minutes." (Buss, 1999, p102). But the interview-data

suggests that men may have to invest between three and six months in

courtship behaviours before they get the opportunity to mate. Whilst

this is much less than the nine months a woman devotes to pregnancy

plus the years of postnatal care, there is nevertheless a greater cost

to the male than is sometimes implied. The pre-mating costs for men

seem to have been discounted by evolutionary psychology.

It is often claimed by

evolutionary psychologists that the cost of mating for men are

relatively slight. For example: "A man in human evolutionary history

could walk away from a casual coupling having lost only a few hours or

even a few minutes." (Buss, 1999, p102). But the interview-data

suggests that men may have to invest between three and six months in

courtship behaviours before they get the opportunity to mate. Whilst

this is much less than the nine months a woman devotes to pregnancy

plus the years of postnatal care, there is nevertheless a greater cost

to the male than is sometimes implied. The pre-mating costs for men

seem to have been discounted by evolutionary psychology. A small,

but significant, proportion of women in long-term relationships engage

in short-term matings (see figure). There must have been some selective

advantage for women to engage in short-term mating otherwise the

inclination to engage in this behaviour would never have had a

selection advantage for men. Buss (1999)

distinguishes between different types of explanations for female

short-term mating that have some experimental support in the human and

animal literature:

A small,

but significant, proportion of women in long-term relationships engage

in short-term matings (see figure). There must have been some selective

advantage for women to engage in short-term mating otherwise the

inclination to engage in this behaviour would never have had a

selection advantage for men. Buss (1999)

distinguishes between different types of explanations for female

short-term mating that have some experimental support in the human and

animal literature:  To

sum up, I would suggest that the notion of monogamous

females and polygamous males is a myth. I would suggest

that there is more symmetry in the costs and benefits of short-term

mating for both sexes than hitherto acknowledged. It would advantage

the inclusive fitness of both males and females to engage in short-term

mating where the partner offers 'good biology', and any offspring would

be sufficiently resourced to ensure their survival to reproductive age.

Thus:

To

sum up, I would suggest that the notion of monogamous

females and polygamous males is a myth. I would suggest

that there is more symmetry in the costs and benefits of short-term

mating for both sexes than hitherto acknowledged. It would advantage

the inclusive fitness of both males and females to engage in short-term

mating where the partner offers 'good biology', and any offspring would

be sufficiently resourced to ensure their survival to reproductive age.

Thus:

Most of

you will have engaged in courtship behaviour at some time in your

lives. How much have you learnt about this behaviour as a psychology

student? Look up 'courtship' in the index of several psychology

textbooks. How much would you learn about this behaviour in humans

if you read psychology texts? Look up 'cerebellum' in the index of

several psychology textbooks. How much would you learn about this

structure if you read psychology texts?

Most of

you will have engaged in courtship behaviour at some time in your

lives. How much have you learnt about this behaviour as a psychology

student? Look up 'courtship' in the index of several psychology

textbooks. How much would you learn about this behaviour in humans

if you read psychology texts? Look up 'cerebellum' in the index of

several psychology textbooks. How much would you learn about this

structure if you read psychology texts?  Read

Read

Read

Read  Here is a

Here is a  Wilson and Day (1998a)

have postulated a 'male sexual proprietariness'

module that is adapted to protect human male reproductive fitness

against undetected cuckoldry

i.e. a set of behaviours to prevent a man's partner being impregnated

by another man. They suggest that because of paternal

uncertainty, and the cost of paternal

investment, male fitness will be reduced if a male is

cuckolded. Wilson and Daly postulate that male sexual proprietariness

is an adaptation that has evolved through

natural selection to overcome this risk.

Wilson and Day (1998a)

have postulated a 'male sexual proprietariness'

module that is adapted to protect human male reproductive fitness

against undetected cuckoldry

i.e. a set of behaviours to prevent a man's partner being impregnated

by another man. They suggest that because of paternal

uncertainty, and the cost of paternal

investment, male fitness will be reduced if a male is

cuckolded. Wilson and Daly postulate that male sexual proprietariness

is an adaptation that has evolved through

natural selection to overcome this risk.  It is very important to

stress that this is a classic example of the type of proposal that can

generate considerable controversy if the suggestion that something "is"

is mistakenly taken to mean that therefore it is "natural" or "ought"

to be. No evolutionary psychologist is suggesting that male sexual

proprietariness is a "good thing". (Here is a