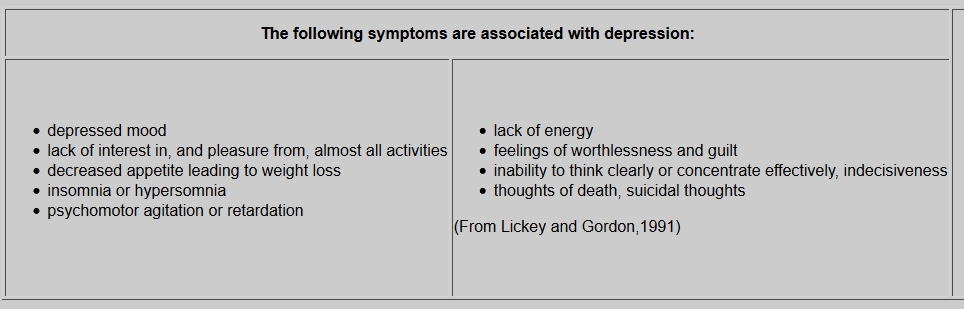

The Nature of Depression

Many people experience sadness following major trauma such as death in the family, divorce or job loss. This is not depression. Depression resembles sadness, but it is more severe and intense. In addition, whereas there is usually a reason for sadness, it can be difficult to account for the severity and intensity of depression in the light of the life events experienced by the sufferer.